Over the course of its extraordinary run as the preeminent photography magazine of its time, LIFE sent its photographers all over the globe to cover the most famous, shocking, thrilling, controversial newsmakers and events of the 20th century. Marilyn Monroe. Steve McQueen. JFK. The Hells Angels. Woodstock. Muhammad Ali. If something or someone was on the minds of LIFE’s millions of readers, or was central at that moment to the great national conversation, LIFE’s photographers were there.

The result? A gallery in which several LIFE photographers recall favorite assignments and the people and places that—captured through their lenses—helped define both the era and their own stellar careers.

In 1965, LIFE’s Bill Ray spent several weeks with a gang that, to this day, serves as a living, brawling embodiment of the American outlaw: the Hells Angels. “I got along with the Angels,” Ray (above, with camera) recalls. “I got to like some of them very much, and I think they liked me. I accepted them as they were, and they accepted me. You know, by their standards I looked pretty funny. Just look at this picture — that’s some kind of a plaid shirt I’ve got on,” he says, incredulity mixing with amusement. “But that was the best I could do to try to fit in!”

Bill Ray Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“This was a new breed of rebel,” Ray remembers today. “They, of course, didn’t have jobs. They despised everything that most Americans pursue — stability, security. They rode their bikes, hung out in bars for days at a time, fought with anyone who messed with them. They were self-contained, with their own set of rules, their own code of behavior. It was extraordinary.”

Bill Ray Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

In a beautifully lit, uncharacteristically quiet portrait, bikers (including the gang’s leader, Sonny, left, with a bandage covering a wound sustained during a bike wreck) and their “old ladies” sit around a table strewn with empty beer mugs and bottles. But, Ray remembers, things could go from placid to edge-of-violence tense in a heartbeat whenever the Angels were involved. “The Berdoo Angels could scare the shit out of anybody. That’s just the way they were. Whenever they walked into a place, they didn’t have to say a word — other groups, other tough-guy bikers, made way for them.”

Bill Ray Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Two of the women riding with the Angels hang out at a bar. Ray has a real liking for this particular photograph. “This is one of my favorites from the whole shoot. There’s something kind of sad and at the same time defiant about the atmosphere. Ruthie (kneeling) is probably playing the same 45 over and over and over again. A real music lover, she was.”

Bill Ray Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

![A nighttime photograph made by Bill Ray outside the Blackboard Cafe looks like it could be a still from a film noir classic. In fact, Ray says that one of the reasons he likes this picture so much is because "it feels like [the great American cinematographer] James Wong Howe could have lit it. But that's the art and craft of the work: photographing on the fly, taking advantage of the available light -- especially when there's very little of it -- and knowing how to capture it."](data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%200%200'%3E%3C/svg%3E)

A nighttime photograph made by Bill Ray outside the Blackboard Cafe looks like it could be a still from a film noir classic. In fact, Ray says that one of the reasons he likes this picture so much is because “it feels like [the great American cinematographer] James Wong Howe could have lit it. But that’s the art and craft of the work: photographing on the fly, taking advantage of the available light — especially when there’s very little of it — and knowing how to capture it.”

Bill Ray Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

![In the spring of 1963, LIFE sent photographer John Dominis to California to hang out with 33-year-old rising star Steve McQueen and see what sort of photos he could get. Three weeks and more than 40 rolls of film later, Dominis had captured some astonishingly intimate and iconic images of the legend-in-the-making -- photos impossible to imagine in today's restricted-access celebrity world."Movie stars, they weren't used to giving up a lot of time," Dominis, now 90, recalls. "In fact, they didn't like to give up hardly time. But I sort of relaxed in the beginning and didn't bother [McQueen and his wife] every time they turned around, and they began to get used to me being there. If they were doing something, they would definitely just not notice me anymore." Above: McQueen and his wife, Neile Adams, enjoy some fast, loud time together.](data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%200%200'%3E%3C/svg%3E)

In the spring of 1963, LIFE sent photographer John Dominis to California to hang out with 33-year-old rising star Steve McQueen and see what sort of photos he could get. Three weeks and more than 40 rolls of film later, Dominis had captured some astonishingly intimate and iconic images of the legend-in-the-making — photos impossible to imagine in today’s restricted-access celebrity world.”Movie stars, they weren’t used to giving up a lot of time,” Dominis, now 90, recalls. “In fact, they didn’t like to give up hardly time. But I sort of relaxed in the beginning and didn’t bother [McQueen and his wife] every time they turned around, and they began to get used to me being there. If they were doing something, they would definitely just not notice me anymore.” Above: McQueen and his wife, Neile Adams, enjoy some fast, loud time together.

John Dominis Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

How was Dominis able to warm up McQueen? “When I was living in Hong Kong,” Dominis remembers, “I had a sports car and I raced it. And I knew that McQueen had a racing car. I rented one anticipating that we might do something with them. He was in a motorcycle race out in the desert, so I went out there in my car and met him, and I say, ‘You wanna try my car?’ We went pretty fast — I mean, as fast as you can safely go without getting arrested — and we’d ride and then stop and trade cars. He liked that, and I knew he liked it. I guess that was the first thing that softened him.”

John Dominis Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

!["We're sitting around the swimming pool," Dominis recalls, "and Steve goes away and he comes back without any clothes on! He just enjoyed being out in the desert, looking at the sun. . . . He was just so natural about everything. There was no time to feel embarrassed, so I shot all the pictures that I needed to shoot. I shot some pictures specially of his backside so we could use them in the magazine, because in most of them he was just [full-on] nude. He wasn't hiding anything."](data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%200%200'%3E%3C/svg%3E)

“We’re sitting around the swimming pool,” Dominis recalls, “and Steve goes away and he comes back without any clothes on! He just enjoyed being out in the desert, looking at the sun. . . . He was just so natural about everything. There was no time to feel embarrassed, so I shot all the pictures that I needed to shoot. I shot some pictures specially of his backside so we could use them in the magazine, because in most of them he was just [full-on] nude. He wasn’t hiding anything.”

John Dominis Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

When Albert Einstein died on April 18, 1955, his funeral and cremation were intensely private affairs, and only one photographer managed to capture the events of that extraordinary day: LIFE magazine’s Ralph Morse. “I grabbed my cameras and drove the 90 miles to Princeton from my home in northern New Jersey,” Morse remembers 55 years later. “Einstein died at the Princeton Hospital, so I headed there first. But it was chaos — so many journalists, photographers, onlookers milling around outside what, back then, was a really small hospital. ‘Forget this,’ I said, and headed over to the building where Einstein’s office was.” Above: Ralph Morse’s photograph of Einstein’s office in Princeton, taken hours after Einstein’s death and captured exactly as the Nobel Prize-winner left it.

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“On the way to Einstein’s office,” Morse says, “I stopped and bought a case of scotch. I knew people might be reluctant to talk to me, and I knew that most people were happy to accept a bottle of scotch instead of money if you offered it in exchange for their help. So, I get to the building and nobody’s there. I find the building’s super, give him a fifth of scotch, and he opens up Einstein’s office so I can take some photos.”

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“I drove out to the cemetery to tried to find out where Einstein was going to be buried,” Morse remembers. “But there must have been two dozen graves being dug that day! I see a group of guys digging a grave, offer them a bottle, ask them if they know anything. One of them says, ‘He ain’t gettin’ buried. He’s being cremated in about twenty minutes. In Trenton!’ That’s about twenty miles south of Princeton, so I give those guys the rest of the case of scotch, hop in my car, and get to Trenton and the crematorium just before Einstein’s friends and family show up.” Above, from left: unidentified woman; Einstein’s son, Hans Albert (in light suit); unidentified woman; Einstein’s longtime secretary, Helen Dukas (in light coat); and friend Dr. Gustav Bucky (partially hidden behind Dukas) arrive at the Ewing Crematorium in Trenton on the afternoon of April 18, 1955.

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Mourners walk into the service for Einstein, passing the parked hearse that carried his body from Princeton. “I didn’t have to tell anyone where I was from,” Morse says of his time spent photographing the events of the day. “I was the only photographer there, and it was sort of a given that if there was one photographer on the scene, he had to be from LIFE.” At one point during the day, Einstein’s son Hans asked Morse for his name — a seemingly insignificant, friendly inquiry that would prove, within a few hours, to have significant ramifications. When Morse got to LIFE’s offices later in the day with his film, he learned that Hans had called the magazine’s managing editor and asked that LIFE not run the photos. The story was, indeed, killed and Morse’s pictures never ran in LIFE.

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Dr. Thomas Harvey (1912 – 2007) was the pathologist who conducted the autopsy on Einstein at Princeton Hospital in 1955. The stranger-than-fiction tale of Einstein’s brain — which Harvey controversially removed during the autopsy, carefully sliced into sections, and then kept for years for research purposes — and the intrigues long-associated with the famous organ, are far too convoluted to go into here. However: On the day that Einstein died, Ralph Morse was able to take a few quick photographs of Dr. Harvey at the hospital. Morse says he’s certain that that is Einstein’s brain under Dr. Harvey’s knife. Then, after a pause, he qualifies that certainty: “You know, it fifty-five years ago. Honestly, I don’t remember every single detail of the day. So whatever he’s cutting there …” Morse’s words hang in the air. Then, mischievously, he laughs.

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

For a few days in August 1969, on a dairy farm in upstate New York, a half-million young people got together to hang out, dance, and listen to music at what became one of the defining events of the ’60s. For LIFE photographer John Dominis, covering the festival became one of the most moving adventures of an amazing 25-year career. “I was much more interested in the people who were there than the musicians,” he recalls. “I liked the music okay, but I liked the kids, and what they were doing, and how they felt about it all.”

John Dominis Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A man sits with two young boys in front of Ken Kesey’s legendary Merry Prankster bus, Further. (See the sign above the windshield.) “I got a nice picture of that painted hippie bus, with a couple of kids and what I think might be their father,” Dominis says. “Whoever painted that thing really did a beautiful job!”

John Dominis Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“I’ll tell you, I really had a great time,” Dominis recalls. “I was much older than those kids, but I felt like I was their age. They smiled at me, and offered me pot … You didn’t expect to see a bunch of kids so nice; you’d think they’d be uninviting to an older person. But no. They were just great!”

John Dominis Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“I’m quite fond of this photo,” Dominis says of one of his most famous images from Woodstock — group of people balancing a plywood board on their heads as shelter from the rain. “You’ll never be able to plan that sort of photo. This is one moment during those three days where they aren’t giggling, or laughing. They are about being uncomfortable. And that somehow makes it work.”

John Dominis Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

In 1947, LIFE’s Ralph Morse went to the Dordogne region of southwest France and, over the course of a few weeks, became the first professional photographer to document the astonishing, vibrant, 18,000-year-old Paleolithic cave paintings there. “The first sight of those paintings was simply unbelievable,” Morse, now 94 and sharp as ever, recalls today. “I was amazed at how the colors held up after thousands and thousands of years — like they were just painted the day before!”

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Ralph Morse and his wife, Ruth, stand outside the entrance to Lascaux with some of the photography and lighting equipment that was eventually hauled down into the cave. “We were the first people to light up the paintings so that we could see those beautiful colors on the wall,” Morse remembers. “Some people, not many, had been down there before us, of course — but with flashlights, at best. We were the first to haul in professional gear and bring those spectacular paintings to life. This little French town simply didn’t have the money, the equipment, the capability to do anything like this after the war. So we did it—and they helped out, because they were as excited as we were to really see what was down there.”

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“Most people don’t realize how huge some of the paintings are. There are pictures of animals there that are ten, fifteen feet long, and more.” Above: A Ralph Morse photograph of what he described, in his notes on the assignment, as a “very important horse” that may well be “the first example anywhere of drawing in modern perspective.”

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“We were there, in the village of Montignac, for at least a week, maybe two” Morse says, chuckling at the memory of his time in the Dordogne more than 60 years ago. “There we were, living in this little French town, heading down into the ground to go to work everyday. It was a challenging project — getting the generator, running wires down into the cave, lowering all the camera equipment down on ropes. But once the lights were turned on … wow!”

Ralph Morse Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

They had fame, reams of money, and fans willing to do wild, unmentionable things just to breathe the same air — but in 1971, LIFE set out to illustrate a different side of rock stars. Assigned to take portraits of the artists with their sweetly square folks, photographer John Olson traveled from the suburbs of London to the San Francisco Bay Area to show that, like most other mortals, these celebrities came from humble backgrounds, with moms and dads who bragged and worried about them every day. “As I remember,” Olson told LIFE.com of his time with the Jackson 5 (above), “they followed my requests to a T, and were incredibly polite.” And what about notorious patriarch Joseph Jackson? “The dad,” Olson admits, “was pretty stern.”

John Olson Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“I got a lot of the drug stories, a lot of the rock and roll stories, and a lot of the anti-war stories,” Olson told LIFE.com of his assignments as a young LIFE photographer. “So when this story came up, I guess I got it because of my age. In hindsight, it was a most unusual time in my life.” Of the stars he photographed for this assignment Olson notes: “I had worked with Ginger Baker (above, with his mom) before, I had worked with Joe Cocker, Grace Slick—and some of these people, the first go-round had been really difficult. Even nasty. But when they were with their parents, they were totally different people. Ginger Baker, who had been terribly obnoxious before, acted like a grown-up. I don’t think it had anything to do with respect for me, so it must have been the parents.”

John Olson Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“They had a parrot in a cage,” Olson remembers of the shoot at Clapton’s grandmother’s home. “Eric’s grandmother, Rose Clapp, left the room, and the parrot talked. It said F—you! I couldn’t believe it. So Mrs. Clapp comes back and I say, ‘The parrot talks.’ And she says, ‘Yes, he says gobble gobble .’ So Eric and I are talking and I ask, ‘Hey, what’s that parrot say?’ and he looks at me like I’m crazy. He says, ‘The parrot says F—you.’ There was a group then called Delaney & Bonnie, and Eric said they stayed there for a couple of weeks and taught the parrot how to say it.”

John Olson/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

On May 19, 1962, screen goddess Marilyn Monroe — literally sewn into a sparkling, jaw-droppingly sheer dress — sauntered onto the stage of New York’s Madison Square Garden and forever linked sex and politics in the American consciousness when she famously, breathily sang “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” to JFK before a crowd of 15,000 — including LIFE’s Bill Ray. “Everybody was in front in the beginning,” Ray recalls of the setup that night inside the Garden, “but it was another one of these events where security says, ‘Hey, we’re really glad you came. Take a few pictures—now get your ass out!’ The Secret Service goons really started clearing everybody out after a few shots. I was afraid of being held in a cattle pen, which is one of the reasons I got out of the group and started moving around on my own.” Pictured: The President arriving at the Garden.

Bill Ray

The chatter about an affair between the president and Monroe was getting louder around the time of the birthday salute, Ray recalls. “People in Washington were always saying there was something going on,” Ray says, “that there was even a Polaroid of Marilyn and Jack in the bathtub performing interesting acts, that Peter Lawford was kind of a go-between, and so on. Nobody really knew. But I knew for sure I was trying to get a picture of the two of them together that night.” Above: President Kennedy and the elites in their box, on the first level facing center stage.

Bill Ray Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

![Trying to get an angle where he might be able to get both Marilyn and JFK in the frame, Ray moved higher up in the Garden . . . and suddenly the moment arrived. "It had been a noisy place, everybody all 'rah rah rah,'" Ray recalls. "Then boom, on comes this light. There was no sound—no sound. It was like outer space." Marilyn was on the stage, taking off her white fur to reveal that scandalous dress underneath. "It was skin-colored and it was really tight. She didn't wear anything underneath it, it was all sewn on, and those Swarovski crystals were sparkling. And she used this long pause.... Then finally, she comes out with 'Happy Biiiiirthday'—she starts the whole breathy thing— and everybody just went into a swoon. I was praying [that I could get the shot] because I had to guess at the exposure. It was a very long lens, which I had no tripod for, so I had to rest it on a pipe railing and try not to breathe." Above: Bill Ray's most iconic photograph, and one of the most famous pictures ever taken of Marilyn Monroe, as she serenades JFK at the Garden.](data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%200%200'%3E%3C/svg%3E)

Trying to get an angle where he might be able to get both Marilyn and JFK in the frame, Ray moved higher up in the Garden . . . and suddenly the moment arrived. “It had been a noisy place, everybody all ‘rah rah rah,'” Ray recalls. “Then boom, on comes this light. There was no sound—no sound. It was like outer space.” Marilyn was on the stage, taking off her white fur to reveal that scandalous dress underneath. “It was skin-colored and it was really tight. She didn’t wear anything underneath it, it was all sewn on, and those Swarovski crystals were sparkling. And she used this long pause…. Then finally, she comes out with ‘Happy Biiiiirthday’—she starts the whole breathy thing— and everybody just went into a swoon. I was praying [that I could get the shot] because I had to guess at the exposure. It was a very long lens, which I had no tripod for, so I had to rest it on a pipe railing and try not to breathe.” Above: Bill Ray’s most iconic photograph, and one of the most famous pictures ever taken of Marilyn Monroe, as she serenades JFK at the Garden.

Bill Ray Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

In 1971, LIFE’s John Shearer spent months photographing the heavyweight champ, Joe Frazier, and Muhammad Ali in the run-up to their March 1971 title bout—a fight billed as The Fight of the Century. “In 1971,” Shearer told LIFE.com, explaining a large part of the fight’s enormous hype, “despite not having held the heavyweight title for years, Muhammad Ali was still arguably the most famous person on the planet.” Above: The challenger commands a press conference at the pre-fight weigh-in.

John Shearer Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“I often felt bad for Joe,” Shearer says, remembering how the 27-year-old world heavyweight champ had few fans in his corner for the 1971 fight with Ali. “In the eyes of so many, he was miscast as the bad guy in the fight. I like this picture of him. It’s a charming moment—but something in his face suggests that if you scratched the surface, you’d find a world of other feelings beneath the surface.”

John Shearer Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

!["The fight in '71 was the last time Ali took Joe for granted," Shearer says. "He simply had not done the hard, hard work required to beat a man like Joe Frazier. Of course, he proved later on—in those battles against George Foreman and Ken Norton and the epic rematches against Frazier—that he was a great, tough champion. But I wonder if, deep down, he hit a point [while training in Miami] where he looked for that fire, that drive, and it just wasn't there. Above: Ali clowns with an aide-de-camp in the back seat of his new Cadillac limo, Miami, February 1971.](data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%200%200'%3E%3C/svg%3E)

“The fight in ’71 was the last time Ali took Joe for granted,” Shearer says. “He simply had not done the hard, hard work required to beat a man like Joe Frazier. Of course, he proved later on—in those battles against George Foreman and Ken Norton and the epic rematches against Frazier—that he was a great, tough champion. But I wonder if, deep down, he hit a point [while training in Miami] where he looked for that fire, that drive, and it just wasn’t there. Above: Ali clowns with an aide-de-camp in the back seat of his new Cadillac limo, Miami, February 1971.

John Shearer Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Frazier—who had an R&B band for years called Joe Frazier and His Knockouts—tests out a band member’s trumpet on the set of NBC’s long-running Kraft Music Hall variety show. “Frazier felt that he was every bit as articulate as Ali,” John Shearer says, “and every bit the showman that Ali was.”

John Shearer Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

His face swollen and bruised after his battle with Ali at Madison Square Garden, heavyweight champion Joe Frazier—stoic even in victory over his nemesis—makes himself presentable. “Frazier didn’t fight by going for the head, which a lot of other boxers did,” Shearer says. “He went after Ali’s body the whole fight, pounding away, taking terrible blows to the head. You know, you keep whacking at the base of the tree, and the tree is going to come down. And that was the story of their first fight.”

John Shearer Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

![A nighttime photograph made by Bill Ray outside the Blackboard Cafe looks like it could be a still from a film noir classic. In fact, Ray says that one of the reasons he likes this picture so much is because "it feels like [the great American cinematographer] James Wong Howe could have lit it. But that's the art and craft of the work: photographing on the fly, taking advantage of the available light -- especially when there's very little of it -- and knowing how to capture it."](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2012/01/ugc11296311-1024x669.jpg)

![In the spring of 1963, LIFE sent photographer John Dominis to California to hang out with 33-year-old rising star Steve McQueen and see what sort of photos he could get. Three weeks and more than 40 rolls of film later, Dominis had captured some astonishingly intimate and iconic images of the legend-in-the-making -- photos impossible to imagine in today's restricted-access celebrity world."Movie stars, they weren't used to giving up a lot of time," Dominis, now 90, recalls. "In fact, they didn't like to give up hardly time. But I sort of relaxed in the beginning and didn't bother [McQueen and his wife] every time they turned around, and they began to get used to me being there. If they were doing something, they would definitely just not notice me anymore." Above: McQueen and his wife, Neile Adams, enjoy some fast, loud time together.](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2012/01/ugc12939513.jpg)

!["We're sitting around the swimming pool," Dominis recalls, "and Steve goes away and he comes back without any clothes on! He just enjoyed being out in the desert, looking at the sun. . . . He was just so natural about everything. There was no time to feel embarrassed, so I shot all the pictures that I needed to shoot. I shot some pictures specially of his backside so we could use them in the magazine, because in most of them he was just [full-on] nude. He wasn't hiding anything."](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2012/01/504113016-674x1024.jpg)

![Trying to get an angle where he might be able to get both Marilyn and JFK in the frame, Ray moved higher up in the Garden . . . and suddenly the moment arrived. "It had been a noisy place, everybody all 'rah rah rah,'" Ray recalls. "Then boom, on comes this light. There was no sound—no sound. It was like outer space." Marilyn was on the stage, taking off her white fur to reveal that scandalous dress underneath. "It was skin-colored and it was really tight. She didn't wear anything underneath it, it was all sewn on, and those Swarovski crystals were sparkling. And she used this long pause.... Then finally, she comes out with 'Happy Biiiiirthday'—she starts the whole breathy thing— and everybody just went into a swoon. I was praying [that I could get the shot] because I had to guess at the exposure. It was a very long lens, which I had no tripod for, so I had to rest it on a pipe railing and try not to breathe." Above: Bill Ray's most iconic photograph, and one of the most famous pictures ever taken of Marilyn Monroe, as she serenades JFK at the Garden.](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2012/01/ugc10472521-678x1024.jpg)

!["The fight in '71 was the last time Ali took Joe for granted," Shearer says. "He simply had not done the hard, hard work required to beat a man like Joe Frazier. Of course, he proved later on—in those battles against George Foreman and Ken Norton and the epic rematches against Frazier—that he was a great, tough champion. But I wonder if, deep down, he hit a point [while training in Miami] where he looked for that fire, that drive, and it just wasn't there. Above: Ali clowns with an aide-de-camp in the back seat of his new Cadillac limo, Miami, February 1971.](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2012/01/008266311-1024x677.jpg)

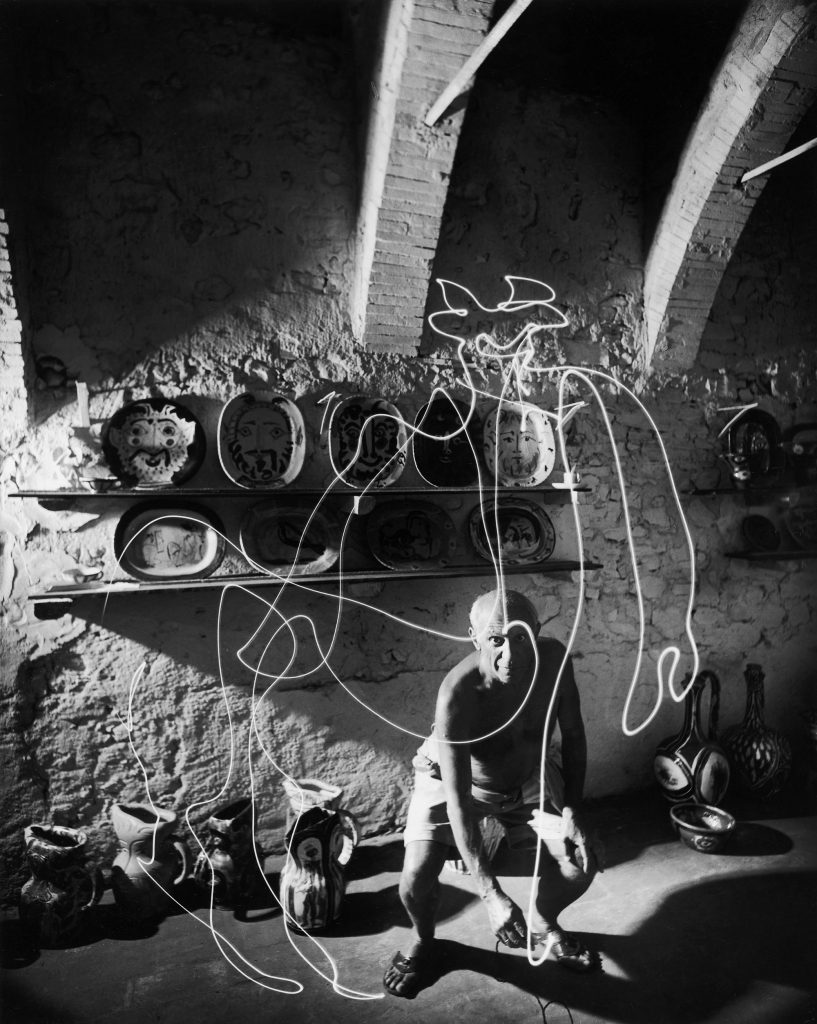

![By setting off a 1/10,000-second strobe light, Mili caught Picasso's intense, agile figure as it flailed away at the drawings. By setting off a 1/10,000-second strobe light, [Mili] caught Picasso's intense, agile figure as it flailed away at the drawings](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2012/01/150316-pablo-picasso-04-1024x1011.jpg)